Write a Net Ionic Equation for the Neutralization Reaction of Hcn(Aq) With Naoh(Aq)

Symbolic representation of a chemical reaction

A chemical equation is the symbolic representation of a chemical reaction in the form of symbols and formulae, wherein the reactant entities are given on the left-hand side and the product entities on the right-hand side with a plus sign between the entities in both the reactants and the products and an arrow that points towards the products, and shows the direction of the reaction.[1] The coefficients next to the symbols and formulae of entities are the absolute values of the stoichiometric numbers. The first chemical equation was diagrammed by Jean Beguin in 1615.[2]

Formation of chemical reaction [edit]

A chemical equation consists of the chemical formulas of the reactants (the starting substances) and the chemical formula of the products (substances formed in the chemical reaction). The two are separated by an arrow symbol (→, usually read as "yields") and each individual substance's chemical formula is separated from others by a plus sign.

As an example, the equation for the reaction of hydrochloric acid with sodium can be denoted:

- 2 HCl + 2 Na → 2 NaCl + H

2

This equation would be read as "two HCl plus two Na yields two NaCl and H two." But, for equations involving complex chemicals, rather than reading the letter and its subscript, the chemical formulas are read using IUPAC nomenclature. Using IUPAC nomenclature, this equation would be read as "hydrochloric acid plus sodium yields sodium chloride and hydrogen gas."

This equation indicates that sodium and HCl react to form NaCl and H2. It also indicates that two sodium molecules are required for every two hydrochloric acid molecules and the reaction will form two sodium chloride molecules and one diatomic molecule of hydrogen gas molecule for every two hydrochloric acid and two sodium molecules that react. The stoichiometric coefficients (the numbers in front of the chemical formulas) result from the law of conservation of mass and the law of conservation of charge (see "Balancing chemical equations" section below for more information).

Common symbols [edit]

Baker-Venkataraman rearrangement

Symbols are used to differentiate between different types of reactions. To denote the type of reaction:[1]

The physical state of chemicals is also very commonly stated in parentheses after the chemical symbol, especially for ionic reactions. When stating physical state, (s) denotes a solid, (l) denotes a liquid, (g) denotes a gas and (aq) denotes an aqueous solution.

If the reaction requires energy, it is indicated above the arrow. A capital Greek letter delta ( [5]) is put on the reaction arrow to show that energy in the form of heat is added to the reaction. The expression [6] is used as a symbol for the addition of energy in the form of light. Other symbols are used for other specific types of energy or radiation.

Balancing chemical equations [edit]

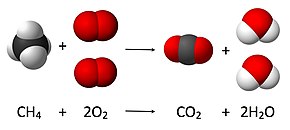

As seen from the equation CH

4 + 2 O

2 → CO

2 + 2 H

2 O, a coefficient of 2 must be placed before the oxygen gas on the reactants side and before the water on the products side in order for, as per the law of conservation of mass, the quantity of each element does not change during the reaction

P4O10 + 6 H2O → 4 H3PO4

This chemical equation is being balanced by first multiplying H3PO4 by four to match the number of P atoms, and then multiplying H2O by six to match the numbers of H and O atoms.

The law of conservation of mass dictates that the quantity of each element does not change in a chemical reaction. Thus, each side of the chemical equation must represent the same quantity of any particular element. Likewise, the charge is conserved in a chemical reaction. Therefore, the same charge must be present on both sides of the balanced equation.

One balances a chemical equation by changing the scalar number for each chemical formula. Simple chemical equations can be balanced by inspection, that is, by trial and error. Another technique involves solving a system of linear equations.

Balanced equations are often written with smallest whole-number coefficients. If there is no coefficient before a chemical formula, the coefficient is 1.

The method of inspection can be outlined as putting a coefficient of 1 in front of the most complex chemical formula and putting the other coefficients before everything else such that both sides of the arrows have the same number of each atom. If any fractional coefficient exists, multiply every coefficient with the smallest number required to make them whole, typically the denominator of the fractional coefficient for a reaction with a single fractional coefficient.

As an example, seen in the above image, the burning of methane would be balanced by putting a coefficient of 1 before the CH4:

- 1 CH4 + O2 → CO2 + H2O

Since there is one carbon on each side of the arrow, the first atom (carbon) is balanced.

Looking at the next atom (hydrogen), the right-hand side has two atoms, while the left-hand side has four. To balance the hydrogens, 2 goes in front of the H2O, which yields:

- 1 CH4 + O2 → CO2 + 2 H2O

Inspection of the last atom to be balanced (oxygen) shows that the right-hand side has four atoms, while the left-hand side has two. It can be balanced by putting a 2 before O2, giving the balanced equation:

- CH4 + 2 O2 → CO2 + 2 H2O

This equation does not have any coefficients in front of CH4 and CO2, since a coefficient of 1 is dropped.

Note that in some circumstances it is not correct to write a balanced reaction with all whole-number coefficients. For example, the reaction corresponding to the standard enthalpy of formation must be written such that one mole of a single product is formed. This will often require that some reactant coefficients be fractional, as is the case with the formation of lithium fluoride:

- Li(s) + 1⁄2 F2(g) → LiF(s)

Matrix method [edit]

Generally, any chemical equation involving J different molecules can be written as:

where Rj is the symbol for the j-th molecule, and νj is the stoichiometric coefficient for the j-th molecule, positive for products, negative for reactants (or vice versa). A properly balanced chemical equation will then obey:

where the composition matrix aij is the number of atoms of element i in molecule j. Any vector which, when operated upon by the composition matrix yields a zero vector, is said to be a member of the kernel or null space of the operator. Any member νj of the null space of aij will serve to balance a chemical equation involving the set of J molecules comprising the system. A "preferred" stoichiometric vector is one for which all of its elements can be converted to integers with no common divisors by multiplication by a suitable constant.

Generally, the composition matrix is degenerate: That is to say, not all of its rows will be linearly independent. In other words, the rank (JR ) of the composition matrix is generally less than its number of columns (J). By the rank-nullity theorem, the null space of aij will have J-JR dimensions and this number is called the nullity (JN ) of aij . The problem of balancing a chemical equation then becomes the problem of determining the JN -dimensional null space of the composition matrix. It is important to note that only for JN =1, will there be a unique solution. For JN >1 there will be an infinite number of solutions to the balancing problem, but only JN of them will be independent: If JN independent solutions to the balancing problem can be found, then any other solution will be a linear combination of these solutions. If JN =0, there will be no solution to the balancing problem.

Techniques have been developed [7] [8] to quickly calculate a set of JN independent solutions to the balancing problem and are superior to the inspection and algebraic method in that they are determinative and yield all solutions to the balancing problem.

Ionic equations [edit]

An ionic equation is a chemical equation in which electrolytes are written as dissociated ions. Ionic equations are used for single and double displacement reactions that occur in aqueous solutions.

For example, in the following precipitation reaction:

the full ionic equation is:

or, with all physical states included:

In this reaction, the Ca2+ and the NO3 − ions remain in solution and are not part of the reaction. That is, these ions are identical on both the reactant and product side of the chemical equation. Because such ions do not participate in the reaction, they are called spectator ions. A net ionic equation is the full ionic equation from which the spectator ions have been removed.[9] The net ionic equation of the proceeding reactions is:

or, in reduced balanced form,

In a neutralization or acid/base reaction, the net ionic equation will usually be:

- H+(aq) + OH−(aq) → H2O(l)

There are a few acid/base reactions that produce a precipitate in addition to the water molecule shown above. An example is the reaction of barium hydroxide with phosphoric acid, which produces not only water but also the insoluble salt barium phosphate. In this reaction, there are no spectator ions, so the net ionic equation is the same as the full ionic equation.

Double displacement reactions that feature a carbonate reacting with an acid have the net ionic equation:

If every ion is a "spectator ion" then there was no reaction, and the net ionic equation is null.

Generally, if zj is the multiple of elementary charge on the j-th molecule, charge neutrality may be written as:

where the νj are the stoichiometric coefficients described above. The zj may be incorporated[7] [8] as an additional row in the aij matrix described above, and a properly balanced ionic equation will then also obey:

References [edit]

- ^ a b IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "chemical reaction equation". doi:10.1351/goldbook.C01034

- ^ Crosland, M.P. (1959). "The use of diagrams as chemical 'equations' in the lectures of William Cullen and Joseph Black". Annals of Science. 15 (2): 75–90. doi:10.1080/00033795900200088.

- ^ The notation was proposed in 1884 by the Dutch chemist Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff. See: van 't Hoff, J.H. (1884). Études de Dynamique Chemique [Studies of chemical dynamics] (in French). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Frederik Muller & Co. pp. 4–5. Van 't Hoff called reactions that didn't proceed to completion "limited reactions". From pp. 4–5: "Or M. Pfaundler a relié ces deux phénomênes … s'accomplit en même temps dans deux sens opposés." (Now Mr. Pfaundler has joined these two phenomena in a single concept by considering the observed limit as the result of two opposing reactions, driving the one in the example cited to the formation of sea salt [i.e., NaCl] and nitric acid, [and] the other to hydrochloric acid and sodium nitrate. This consideration, which experiment validates, justifies the expression "chemical equilibrium", which is used to characterize the final state of limited reactions. I would propose to translate this expression by the following symbol: HCl + NO3 Na NO3 H + Cl Na. I thus replace, in this case, the = sign in the chemical equation by the sign , which in reality doesn't express just equality but shows also the direction of the reaction. This clearly expresses that a chemical action occurs simultaneously in two opposing directions.)

- ^ The notation was suggested by Hugh Marshall in 1902. See: Marshall, Hugh (1902). "Suggested Modifications of the Sign of Equality for Use in Chemical Notation". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 24: 85–87. doi:10.1017/S0370164600007720.

- ^ The symbol is more properly denoted as a simple triangle (△), which was originally the alchemical symbol for fire.

- ^ This symbol comes from the Planck equation for the energy of a photon, . It is sometimes mistakenly written with a 'v' ("vee") instead of the Greek letter ' ' ("nu")

- ^ a b Thorne, Lawrence R. (2010). "An Innovative Approach to Balancing Chemical-Reaction Equations: A Simplified Matrix-Inversion Technique for Determining the Matrix Null Space". Chem. Educator. 15: 304–308. arXiv:1110.4321.

- ^ a b Holmes, Dylan (2015). "The null space's insight into chemical balance". Dylan Holmes. Retrieved Oct 10, 2017.

- ^ James E. Brady; Frederick Senese; Neil D. Jespersen (December 14, 2007). Chemistry: matter and its changes. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN9780470120941. LCCN 2007033355.

Write a Net Ionic Equation for the Neutralization Reaction of Hcn(Aq) With Naoh(Aq)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemical_equation

0 Response to "Write a Net Ionic Equation for the Neutralization Reaction of Hcn(Aq) With Naoh(Aq)"

Post a Comment